photos: Mark Alesky

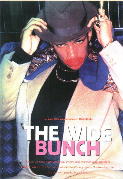

| THE WIDE BUNCH | |

| Tense, nervous and paranoid, Tricky has emerged from the dark heart of the Bristol beat with an extraordinary album that is almost as strange and perplexing as he is | |

| TEXT: Sean O'Hagan PHOTOGRAPHY: Mark Alesky | |

| The living room

of Tricky's temporary west London abode is spar tanly furnished, strewn

with the usual debris of the nomadic 'musi cian: empty Lucozade cans and

full ashtrays, record sleeves and rented videos, discarded cigarette filters

and torn Rizla packets. Behind the door, a new Fender guitar is propped

up next to a tiny practice amp. There is a framed photo of Rakim (of Eric

B &...) on the fireplace and a PJ Harvey poster tacked up on an otherwise

bare wall. A film soundtrack plays on the stereo and a live broadcast from

Parliament on the television; as the soundtrack music fades out, the listless

ebb and flow of MPs going through the motions fades in. From an adjacent

room, the rumble of a repetitive bass and drum coda leaks into an already

overloaded sound scape. Ambient chaos. Absolutely perfect.

"People use the word 'chaotic' a lot," Tricky laughs, as he settles himself in an armchair and immediately begins dismantling a cigarette, "but the records only sound chaotic because I honestly don't know what I'm doing. Technically, I'm totally naive, and emotionally, I'm fucked up. The music is just a way to try and work out what is going on inside my head" By now, you'll have heard three examples of Tricky's chaos therapy: "Ponderosa", "Aftermath" and "Overcome", records that may have surprised anyone expecting a variation on the finely honed, immaculately tailored music of his former cohorts Massive Attack. What the singles hinted at, the album confirms. "Maxinquaye" - "It's a meaningless word" - is a mesmerising record, by turns unhinged, delirious and darkly |

sensual. Though Tricky

is justifiably miffed by the lazy journalistic minds who have already filed

him under Trip Hop, Bristol Division, his music does share a sensibility

with some of Massive's work ("Safe From Harm", "Daydreaming") and even

- though he won't thank me for saying it - some of the less mannered moments

from Portishead's debut. ("They aren't doing nothing that The Wild Bunch

and Smith & Mighty weren't doing back in the days.") What sets Tricky

apart from his contemporaries is that his music possesses a heart of darkness

that doesn't just beat subliminally in the background but bleeds and seeps

into every available space. At first, the album sounds wilfully chaotic

but, with every play, slowly reveals its warped beauty and cohesive inner

logic. Of all the albums yet to emerge out of England's increasingly intriguing

post-hip hop nation, "Maxinquaye" is easily the weirdest and certainly

one of the most powerful.

First up, there's the slippery subject matter: sexual angst and addiction rubbing up against a seemingly all-pervasive sense of emotional dislocation. A song like "Suffocated Love" drips dark sex and sensuality as Tricky teases out maximum suggestion from lines like "It's too good / it's too nice / She makes me finish too quick / Is it love? No, it's not love / She turns my sexual trick". (Unsurprisingly, he cites Prince as a big influence and has ear- marked "When Doves Cry" as a possible future cover.) Then, there's the extraordinary music: scrapyard beats, dense multi-layered samples and a consistent feeling that everything is constantly on the verge of falling apart. |

| "Technically I'm totally naive, and emotionally, I'm fucked up. The music is just a way to work out what is going on inside my head" |

| Finally,

there's Tricky and Martina's twinned and twisted vocals: his mischievous,

wacked-out rapping style meshing perfectly with the cracked, punkish beauty

of her singing voice. If there is a consistent worldview explored on "Maxinquaye",

it is the anxiety of the everyday, an abiding sense of unease that is articulated

- and amplified - by a mind blurred and blunted by bad weed and terminal

paranoia. "Lately," Tricky admits matter of factly, "life has been getting

to me. I honestly think that writing lyrics is the only thing that has

kept me sane. I'm not saying that lightly or in any rock'n'roll way. It's

just the plain simple truth."

It's difficult to ascertain if Tricky was always of a pessimistic persuasion. He is sketchy about his formative years in Bristol but hints, in passing, at a troubled childhood. "That's why I'm not stable," he tells me at one point, "I was a problem child and you can hear that in the music." He began rapping while still at school, hanging out with a fledgling posse whose other key movers later mutated into The Fresh Four. Later still, he inevitably crossed paths with the now legendary Wild Bunch (whose core members included 3D, Mushroom and Daddy G from Massive Attack and producer extraordinaire Nellee Hooper). He remembers nervously "dropping a few rhymes with The Wild Bunch at an early Smith & Mighty ware house jam in St Pauls. There was always a posse around the decks and I'd always be trying to scrounge the mic off them guys even before I'd written a rhyme of my own." When The Wild Bunch split, Tricky went on to become an associate member of Massive Attack and, both as a writer and rapper, was an integral part of the chemistry that made "Blue Lines" such a groundbreaking work. Though he turned up on two songs on last year's excellent "Protection" album, he was already too deep into his solo work to go out on the road with them for their recent live shows. "We're really occupying different spaces now musically." The musical distance between them is perhaps best illustrated by their |

separate versions

of "Karmakoma", a Tricky-penned track first heard on "Protection" which,

subsequently retitled "Overcome", has resurfaced in radically different

form as Tricky's most recent single. Where Massive's version is the most

buoyant track on their album, Tricky's take is an altogether more dark

and dreamy affair that highlights the strange and startling instrument

that is Martina's voice. "Basically, I went looking for a singer 'cause

I didn't want to be known just as a rapper," Tricky elaborates, "and she

just turned up. She was sitting on a wall outside my house in Bristol and

we got chatting."

Martina is a woman of few words, most of them measured by sighs and long, thoughtful pause. She used to be "a sort of jazz singer" and wants to go to college to study oceanography. On just about everything else, she seems hazy or blissfully uninterested. Or both. She remembers that the first song they recorded together was called, intriguingly, "Shoebox", that Tricky's songs are "funny but not happy", and that her only intention in singing them is "to sound like a normal English person but a bit dislocated". In this, she has certainly succeeded. How did she feel, I wondered, singing lines like "I'll fuck you up the ass / Just for a laugh / With my quick speed / I'll make your nose bleed"? "I don't think I can shed any light on the songs because I only sing them. I think I wrote about four lines on the whole album. (pause) But, you know, they're Tricky songs - dark and truthful. I think they reflect the way a lot of people feel right now, but they're also a bit otherworldly. (pause) I guess that's because Tricky's an alien." Sitting in his apartment, flanked by a row of rented videos from the harder end of the home viewing spectrum - Eubank, Al Capone, Good Fellas - Tricky does come across as someone who, if not an alien exactly, certainly seems alienated. Not to put too fine a point on it, he looks a lot heavier these days, his shaved head, tattoos and newly-acquired |

| "There's money and death in the air. Walk down the street and you can smell it. We're that close to it all the time and people don't see it. What I'm talking about is the evil that's in the air" |

| nose ring lending that

mischievous boxer's face an altogether more threat ening aspect than the

impish persona that graced Massive Attack's music. "I guess I can come

across as a bit of a heavy," he grins when I ask him if his look reflects

his current state of mind. "I think I get some of it from my uncle. He

was a heavy dude, bit of a schizo lunatic from what I've heard. But, he

was respected because people feared him. I think I definitely have that

side of him in me."

Luckily, it only seems to surface in the music. What, I ask him, was he thinking of when he was writing the aforementioned lines from the awe somely heavy "Abbaon Fat Tracks"? "Erm. That was one of my anti-people days. See, I let people get to me more than I should. It took me a while to suss out how cliquey the scene is in London. All these people in their little cliques, patting each other on the back. I don't wanna be a part of that. That's what that lyric is all about. It just sorta spewed out of me." There are quite a few moments on "Maxinquaye" that are fired by the same sort of disgust at the world in general, and the world of music in particular. Sometimes, Tricky sounds vengeful ("Abbaon Fat Tracks", "Brand New, You're Retro"), at other times, just plain be leaguered ("Hell Is Round The Corner", "Struggling"). Mostly, though, he comes across like some strange character caught in an urban night mare from which there is no escape (virtually every track on the album "That's what I feel like a lot of the time. I think it's because I'm a bit of a loner and I'm always talking to myself in my head or else I'll go out on my own and talk to total strangers in clubs and, basically, do their head in. It's pure bollocks but it was the sort of tliing that was happening quite a lot while I was making the album. Just feeling disconnected from things. Instead of staying in and writing lyrics, I'd go out and get pissed up and charged up and look at girls or whatever. See, |

I'm weak

and that disgusts me. There's a lot of that self-disgust in the lyrics."

There is also an abiding sense of paranoia that, as he has admitted before, often comes from his over-indulgence in the demon weed. If you were to trawl about for comparisons, Sly Stone's "There's A Riot Goin' On" (actually a coke-fuelled inner journey) or Lee Perry's "Bad Weed" are records infected with a similar sense of unease. On "Maxinquaye", spliff seems to have been actively utilised as a creative catalyst that, unlike most of the stoned doodlings that comprise the "trip hop" school of blunted beats, actually sharpened, rather than dulled, the protagonist's point of view. "I used to be a preacher for spliff," Tricky tells me, "but something happened. Either it's gotten a lot stronger than it used to be or my tolerance has gone down. Now, two spliffs and I get dark and insecure and I could do things to people." What kind of things? "Bad things, guy. If you take too much spliff, it adds to the pressure instead of lifting it. You know how Rastas talk about everything being dread? Well, now I know what they mean. Too much spliff makes you see how dread things are. There's money and death in the air. Walk down the street and you can smell it. We're that close to it all the time and people don't see it. What I'm talking about, I suppose, is the evil that's in the air." There's a line in "Ponderosa" where you say you're in "the devil's company"; is that the sort of evil you're talking about? "Well, that's about total paranoia from drinking and smoking too much and going way over the top. Sometimes, I do that and watch a load of gangster movies and I really feel like I'm keeping the devil's company. I get so negative and evil. I mean, paranoia is a powerful force if you can use it creatively but, sometimes, it just takes over. It's not good, but it passes. |

| The one cover version on the album is a thrashed-up take on Public Enemy's "Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos" where a barrage of suitably jagged samples detonates an afready coruscating noise courtesy of a Mancunian metal band called ETY. Alongside Rakim, Chuck D is perhaps the least surprising member of Tricky's small but eclectic list of key influences ranging from Billie Holiday to The Specials - "Terry Hall can't sing but he sounds brilliant" - via Kate Bush, Prince and Polly Harvey. "Music," he says, looking genuinely pained, "doesn't uplift me the way it used to. I watch MTV and I get angry at all the crap that's out there. Or else, I hear something like the Polly Harvey album and it's so wicked that it makes me jealous. Sometimes I think that's all that keeps me going - bitterness and anger." If this if true, Tricky's music is proof that darkness can be transmuted into light. Despite, or maybe because of, its black heart and creeping sense of unease, it is a work of rare beauty that insinuates | its way into the sub conscious like some slow-release drug. In many ways,

"Maxinquaye" is a soundtrack for our times, a record that speaks, in whispers

and screams, about the lurking sense of anxiety that stalks everyone who

senses that the world we live in has become an immeasurably sadder, darker

and, yes, more chaotic place. "When I was younger," Tricky tells me near

the end of our meeting, "people used to say to me, 'Get a life' and I'd

always wonder what exactly that expression meant. Now I know. I go to clubs

and I see people who are lost - spiritually, emotionally, psychologically.

They're lost and the thing is they don't even know it. At least I know

I'm lost. What I'm trying to do with my lyrics a lot of the time is find

myself. I guess I'm just trying to get a life...".

"Maxinquaye" is released by Fourth & Broadway on Feb 13 |

| analyze me (Tricky) | |

| Tricky solo discography | |

| Tricky biography |