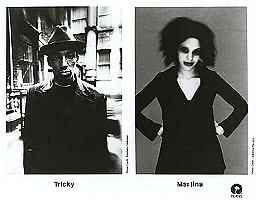

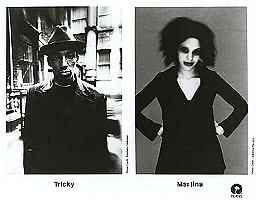

Like the critically acclaimed, genre-crashing debut, the new LP is marked by homemade bits of dance, soul, ambient, dub, blues, crunching guitars and other random snippets of noise, all woven together with Tricky's hip hop inspired, cut-and-paste production style -- resulting in a soundscape that he so succinctly describes as "mutant." And once again, ghostly vocals from Maxinquaye's Martina and Tricky's own, dead-pan rap-growls writhe with pain and passion atop his post-modern, sonic pastiche.

"The lyrics on Pre-Millennium Tension are furious. And musically, I think it's the closest thing to punk in a long time. Not punk as in loud guitars, but as in the energy, and the whole attitude -- that I can just do or say whatever the f--k I want."

If the 28 year-old Bristol-born artist comes off a bit cocky, he's allowed. In late '94, Maxinquaye debuted on the UK charts at #3 and held fast at the top of the UK top 40, an unprecedented feat for an album straying so far from the usual British pop, rock and dance flavors of the hour. Hitting gold status, the LP garnered a whirlwind of praising ink in mags like NME, Melody Maker and The Face before crossing the Atlantic, only to be received with open arms by a dotting American press. Use of words like "genius" and "brilliant" were all too common. Maxinquaye landed on "year's best" list in publications across the States, while a legion of acts and labels scurried to jump on the "trip hop" bandwagon Tricky had set in motion.

"Since Maxinquaye came out, the word 'weird' has become fashionable," Tricky grins. "It was an anomaly then, not now. That's chart music now. Maxinquaye ia a pop album. Mad, isn't it?! That's why I have to move on."

In fact the "trip hop" moniker which he's been crowned has never been one he's worn too happily.

"My foundation was hip hop, but my hip hop was weird. So it became this thing called 'trip hop'." But I don't want to be pigeon-holed. I've been on the rock charts, hip hop charts, blues charts, jazz charts -- I like the fact that I can bounce. I don't agree with the name 'trip hop.' If I supposedly invented it, why not call it Tricky-hop? If I'm the 'Majesty of Trip Hop,' f--k it -- I want to change the name. I'd love to know who came up with that term."

The real irony, though, is that his wide-ranging songs don't really typify the rhythmic, hallucinogenic "genre" he's credited with pioneering.

"It must be confusing when people hear a f--king crunching metal guitar riff, like 'This must be Trick-Trash!'" He gives a hearty raspy laugh. "It even confuses me!"

The labeling doesn't stop at his music. The media has regularly tagged him as a dark, moody, wounded creature, linking his often twisted lyrics to the death of his mum at age four, an absentee dad and teenage scraps with the law.

Recalling a childhood filled with wicked laughs and fond memories, Tricky is quick to dispel myths about his background: "They've tried to make me look like a real villain. I was just mischievous. People find my music dark and moody, I suppose, so if I say I sold a bit of weed, that bit of weed becomes hundreds of ounces and with hundreds of ounces there's guns... and things get carried away. Since my music is extreme, my life is supposed to be extreme. I'm actually very very very normal. Cheese sandwich normal."

As a teen, Tricky started rapping at underground parties with the Wild Bunch, a local MC/DJ crew which later branched into the soul dance act Massive Attack. As a surrogate member, Tricky wrote and performed three tracks on their first album Blue Lines, and did vocals and lyrics on two tracks of thier follow-up Protection.

Moving to London to pursue a solo career, he pressed up and passed out a few thousand copies of "Aftermath," a jangly mesh of strings, flutes and rock riffs he'd created three years before with Bristol singer Martina. The record's thunderous street buzz led to his deal with Island and two subsequent boundary bashing LPs.

While Maxinquaye interspersed indie rock, metal and alterna-pop amidst its disturbed slowjams and quaalude funk, Pre-Millennium Tension is even more eclectic. Songs jumped from the harmonica driven jungle rock of "Sex-Drive" to a tripped out interpretation of cajun blues on "My Evil Is Strong"; from futuristic reggae on "Christiansands" to "Bad Things," a take on gangsta rap; from the choked frustrated rhythem of "Vent," to "Ghetto Youth," a Jamaican patois spoken word type thing recited by some random cat named Sky who Tricky met while cutting the album in Jamaica.

Musically, all eleven cuts are imbued with raw organic and passionate quality often missed in technologically based music. Instead of gluing together found sounds and loops, Tricky came up with his own on his shoe-box sized QY20 sequencer. Like a road paved with hundreds of different oddly sized bricks that somehow interlock, these homespun bits and pieces were then sampled and pasted together.

"That's why a lot of it speeds up and slows down, 'cuz I'm playing little melodies, riffs, drum patterns, strings straight from the sequencer. It's live music." He's emphatic: "when people say I don't write music, I say that's exactly what I do."

Lyrically, some tracks deal with specific topics -- "Makes Me Want To Die" chronicles the effect of the hydroponic high from chemically grown mary jane, the melancholy "Piano" swipes its plotline from the late '70s French film A Little Romance. Others Tricky admits with a wink are "just loads of jumbled word with no coordination at all." Obscured, "low-fi" vocals were often cut at the production console instead of in the recording booth "because when I get a vibe, I can't wait 20 minutes for someone to set up a mic and move all that shit in there."

Finally, just a Maxinquaye featured a ripping cover of Public Enemy's "Black Steel," the new project isn't without its hip hop tributes featuring revamps of Chill Rob G's "Bad Dream" and Erik B. & Rakim's "Lyrics Of Fury." On the flip side "Tricky Kid," with it's over-the-top attitude (and a lyrical nod to, of all bands, The Presidents Of The United States Of America), is a piss take on over popular braggadocio raps. The resounding line, "It's a new age," hints at the songs underlying message.

Explains Tricky: "Its is a new age, unsafe, where no one's the king of anything -- hip hop, jungle, trip hop. We're really vulnerable. So we all have to keep on moving."

That's never been a problem for Tricky, who, between albums released the critically lauded compilation Nearly God boasting the likes of Neneh Cherry, Alison Moyet, Terry Hall, and Bjork singing over Tricky produced tracks, as well as Grass Roots, a hip hop/R&B tinged EP with a Tricky spin.

He collaborated on two songs on the new Crow soundtrack, one with Bush, the other with Wu-Tang spin-off, The Gravediggaz. He has also worked independently with the Wu's RZA ("the Mozart of hip hop," according to Tricky) and forged tracks and remixes for Bjork, Cherry, Garbage, Elvis Costello and Porno For Pyros. He's working on an album with Grace Jones, to be released on his own Durban Poison label (through Island); has produced an album featuring his hand picked crew of British and American rappers, called Drunkenstein, soon to be released; and is currently exec-producing Product Of The Enviroment, a series of spoken word tales by former Bristol gangsters set to music.

Amidst his mad studio schedule, he also fits in Tai Chi and shares responsibilities with Martina for their baby daughter.

Says Tricky: "People say I'm prolific. I don't think I'm prolific. It's just that I can't concentrate on anything for too long. Making music is like painting, drawing when you were a kid. You take a crayon, draw a line. Then when you've had enough of that line you do another line. It's the best fun."

# # #

For more information please contact Susan Mainzer at Island LA, 310-288-5327.